Evolutionary Water Bodies

Narratives around Bahrain’s Ancient Water Practices

The name originates from Arabic translating to “two seas” or islands with two kinds of water: sea water and spring-sweet water.

Bahrain / البحرين

Source: Expedition Magazine, Penn Museum

Source: Bahrain Authority for Culture & Antiquities

Source: The British Museum

Source: Alayam Newspaper

Resources:

“Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities - Kingdom of Bahrain | Eternal Springs.” n.d. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://culture.gov.bh/en/events/AnnualFestivalsandEvents/HeritageFestival/HeritageFestival2017/EternalSprings/.

Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. n.d. “Barbar Temple.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/1570/.

“Cylinder Seal | British Museum.” n.d. The British Museum. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1891-0509-2553.

“Enki/Ea (God).” n.d. Text. CHECK with Nicole***. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://build-oracc.museum.upenn.edu//amgg/listofdeities/enki/index.html.

“Expedition Magazine - Penn Museum.” n.d. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/the-indus-civilization-and-dilmun-the-sumerian-paradise-land/.

Hojlund, Flemming, Pernille Bangsgaard, Jesper Hansen, Niels Haue, Poul Kjaerum, and Dorthe Danner Lund. 2005. “New Excavations at the Barbar Temple, Bahrain.” Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 16 (2): 105–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0471.2005.00248.x.

حسين, المنامة-حسين محمد. n.d. “العيون الطبيعية البرية.” صحيفة الوسط البحرينية. صحيفة الوسط البحرينية. Accessed December 15, 2022. http://www.alwasatnews.com/news/326133.html.

Water has always been a fundamental component within the islands of Bahrain, beginning with one of the earliest civilizations in the Dilmun period. Perception of water has evolved over time, moving from the sacred, to the social, and towards a commodified resource under threat, where our drive for comfort has normalized the over-consumption of our resources.

Most conversations around water stress are dominated by technical innovations and water processing efficiency; however, there’s a disregard to the country’s rich cultural water heritage in that conversation. This raises a series of inquiries regarding how we culturally and as a society consume, engage, interact, and perceive the water we have access to.

Today, the production of water, through industrialized methods, creates a disconnect between the consumer and the resource consumed. Although, looking back at the country’s water practices we can observe a clear appreciation and respect towards the resource. Why is that?

Reflecting on Dilmun, the mythology and narrative of that civilization is rooted in water. Enki, one of Dilmun’s prominent gods, also known as the Sumerian Poseidon. Upon his arrival to the land, he fills it with freshwater turning Dilmun into fields of greens. Today, what remains from that mythology is a series of temples built around watersprings; Barbar Temple is believed to house a shrine to Enki, the water god. People of that era used the water from the springs in bathing, blessing, and purifying their bodies due to the sanctity associated with it. At this time, water was highly regarded as a sacred resource connecting individual to god.

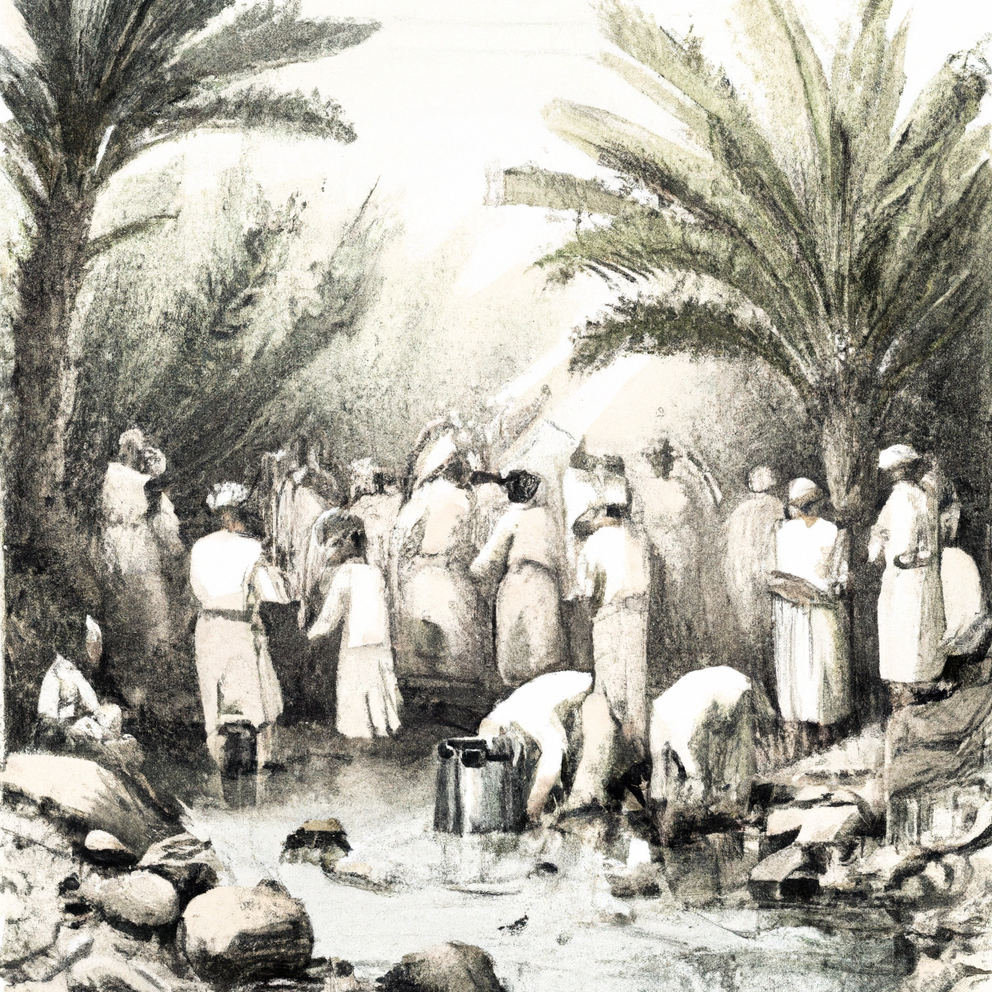

Looking at the early 20th century, water was intrinsic to the social everyday life of the people. Communities would go to the watersprings to wash their garments and cookware, to collect water, and to swim. Clay vessels or leather satchels would be used to collect water either from the springs or from the sweet-water present in the sea, where villagers would go on to their communities to sell their collection. This type of water infrastructure creates a sense of connection between consumer and resource consumed, imposing a responsibility and mindfulness towards it.

Today; however, the lack of engagement between consumer and resource creates a gap of understanding and consciousness. How can our industrialized methods of water production yield to the same spiritual, communal, and individual engagement with water that was present before? How can we re-introduce our ancient water heritage to our modern industries? How can we alter our perception of what water represents and means to us in the 21st century?